Turbo-engine models are more expensive, and lower tax benefit does not reach consumers

By Pedro Kutney | Translated by Jorge Meditsch

At a moment when sales of 1.0 cars return to history’s highest levels – 58% of registered automobiles from January through September – it’s time to discuss again if these vehicles deserve the incentive they receive, paying less IPI (industrialized products tax) than any other models with larger engines, even more efficient.

The last time 1.0 car sales reached the current index was in 2003, after reaching almost 70% in 2001. After 2004, there was a reduction in the difference between the taxation of 1.0 vehicles and the others, and it made the little engines market share gradually fall over the following years to 32.7% in 2016.

After this, with the introduction of 1.0 turbo models, the sales went up again until reaching the current 58%, showing the combination of power and economy is currently an important reason to attract the Brazilian customer – no longer just the price, as all models became too expensive for what they offer.

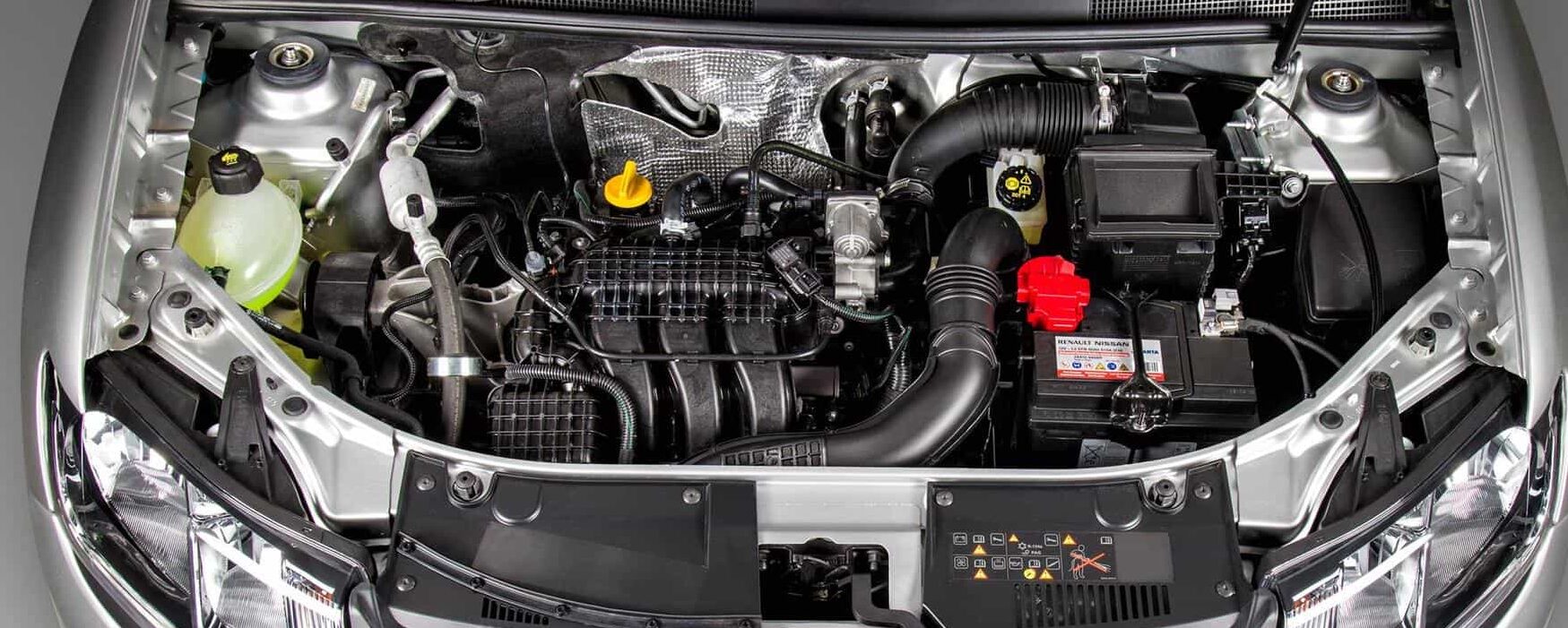

Technological evolution increased the 1.0 engines power from a mere 50 cv, at the beginning of the 1990s, to near 70 cv, for the naturally aspired, and 115 cv to almost 130 cv for turbocharged.

Nonetheless, advances as supercharging and direct injection also caused prices to increase, making the tributary difference lose the reason to exist, as currently brand-new cars of any kind are for few -very few people.

Of the 1.0 cars currently sold in Brazil, there are 13 naturally aspirated models from seven brands and 12 turbocharged from four manufacturers located in the country. Of the ten best-selling automobiles from January through August, six have 1.0 engines or offer it as an option, and three have only aspirated versions.

Distortions

In the beginning, the artifice of reducing taxation for 1.0 cars helped to expand the market and motorization of the country, especially after 1993 with the introduction of the 1.0 popular car, which had the IPI reduced to 0.1% for two years.

Sales increased, in fact – over 32 years, more than 25 million 1.0 cars were sold in Brazil, 45% of all automobiles licensed in the period. But this policy limited vehicle technical development for many years and created low-quality products, with low or no export potential, that still prevail in Brazilian streets.

Among the so-called automotive “jaboticabas” (a fruit known for existing only in Brazil), one of the most enduring and prejudicial is the reduction of IPI tax exclusive for 1-liter cars. In three decades, the 1.0 models went through no less than 18 IPI taxation changes, up and down, but continued paying less in a tax policy that lost its sense and should end.

The 1.0 cars do not deserve to receive a tax incentive limited to engine displacement because they do not benefit society and are not always more efficient than larger engine vehicles. What should be encouraged, so, is the vehicle’s energy efficiency, not engine displacement, power or size.

Another point is that, with the introduction of turbocharging over the last years, the 1.0 turbocharged models became more expensive than similar versions equipped with larger displacement aspirated engines, such as 1.3 or 1.6-liter, which pay more IPI. It means that a 1.0 turbocharged car does not deliver to the customer the benefit of the lower taxation – this benefit is currently pocketed by the manufacturers to increase profit margins.

Currently, a 1.0 gasoline-ethanol flex-fuel car, either turbocharged or aspirated, pays 5.2% as IPI, compared to 8.3% for any other flex-fuel model with engines over 1.0 through 2.0-liter.

Another distortion: gasoline cars pay more IPI than flex-fuel models, even more than 60% of the bi-fuel models in the country use only gasoline, as ethanol price is too high.

Another Brazilian tributary system’s inconsistency is that electric and hybrid vehicles have three classes of taxation based on energy efficiency and weight, varying from 6.8% to 18.8% for hybrids and 5.3% to 13.5% for pure electrics.

This means that the hybrids, much more economical than the 1.0 combustion-engine models, pay more tax. Is there any sense in continuing this way?

Pedro Kutney is a journalist specialized in economy, finances and automotive industry. He signs the column Observatório Automotivo, specialized in the automotive sector, and works as editor of AutoData magazine, With more than 35 years of profession, he was editor of the Automotive Business portal, Automotive News Brasil and Agência AutoData. He was also Finance assistant editor at Valor Econômico and reporter and writer of magazines Automóvel & Requinte, Quatro Rodas and Náutica.

Assim como a Anfavea, o presidente da entidade, Marcelo Godoy, também não apoia pleito da…

Empresa tem acordo de participação e produção de carros na fábrica paranaense da Renault

Crossover elétrico tem duas versões de motor e autonomia de até 600 km

Há um ano no programa AutoEsporte, antes era chefe de Imprensa/Produto na Stellantis

Negócio envolve um centro de P&D e uma unidade de produção; empresa atuará de forma…

Da produção limitada a 660 unidades, dez desembarcarão por aqui